I CLIMB. It is what I do. I am a four season Climber. I climb, then climb harder, Then send it. This is not a place for posers or trolls.

About Me

- Pyro

- I am who I am. Don't try to change me, It won't work! Like me, love me, or get the hell out of my way! I have been described as an opinionated asshole in the past. Mostly by people that didn't like hearing what I had to say. I have also been decrribed as a very good friend to have when your butt's in the fire. If you are still reading this then maybe one day you will see that side of me, as you have passed the first test, you have listened.

Sunday, November 28, 2010

A Taste of Pyro's Rock

Trees go wandering forth in all directions with every wind, going and coming like ourselves, traveling with us around the sun two million miles a day, and through space heaven knows how fast and far!

Keep close to Nature's heart... and break clear away, once in awhile, and climb a mountain or spend a week in the woods. Wash your spirit clean.

Keep close to Nature's heart... and break clear away, once in awhile, and climb a mountain or spend a week in the woods. Wash your spirit clean. A few minutes ago every tree was excited, bowing to the roaring storm, waving, swirling, tossing their branches in glorious enthusiasm like worship. But though to the outer ear these trees are now silent, their songs never cease.

Everybody needs beauty as well as bread, places to play in and pray in, where nature may heal and give strength to body and soul.

How glorious a greeting the sun gives the mountains!

Wednesday, November 24, 2010

Trip Report for Eagle Rock, SC #7.

Ok, I have been a little remiss in posting this trip report. It is due to the fact that I have been busy and haven’t had the time to sit in front of the computer to write. But here we go.

I have not been feeling my best in the last week mainly due to the fact that I couldn’t walk from Tuesday to Friday. This is due to the weather change I think. It has been cold and damp here in VA. But Sat I got up and was feeling a little better so after getting out of work at 1730hrs I came home and threw the gear in the truck and got out on the road. I stopped at Wal-Mart to pick up some propane cylinders for my stove and some General Soe’s chicken for my gut and then I was west bound for the Promised Land.

I arrived in smoke hole around 2000hrs and did the link up with mike G at the campfire. This is also where I met Cindy B and Phoebe, who both ROCK. Literally, they are both climber’s. After hanging out at the fire for a while we moved down to the camp site where I talked Mike into helping me set up my new Mountain Hardware tent. Between the two off us we got it set up. One day I will learn to do pre-trip checks on the gear. But we got it set up with no problems. Matt was right this tent rocks. I stayed dry and warm and no condensation at all built up over the night. Ok that was my little plug for Mountain Hardware for this blog. (Mt. Hardware, you can send the check to my Home address) Ok now back to the trip report, after setting up the tent Mike and I did the typical camp thing with everyone and stood around and talked and just had a plain old good time. I had also brought a couple of Magic Hat’s with me in the ruck that I shared with everyone. Magic Hat # 9 has to be one of my favorite beers of all time (Magic Hat, you can also send the check to my home address).

Sunday morning I woke up after one of the best nights of sleep that I have had in a long time. It had to be the river flowing right next to the campsite but I slept very well. After everyone was up Mike, Cindy, and Pheobe went up to Mike’s and I hung out at the campsite and sorted my climbing gear for the day and packed up my tent, fart sack and puss pad. Then I just hung out and enjoyed the wonderful scenery that was all around me. I got some really good pictures of the sun on the rocks and the river. When everyone got back Mike had made breakfast for everyone. I’m here to tell you Mike makes the best breakfast burritos that I have ever had in my whole life. So after filling our stomachs with really good food and coffee it was time to fill the hole in my soul for some new rock. So it was off to SC#7!

We left Eagle and set out for SC#7. After arriving we loaded up the gear and headed up for the crag on the wonderful trail that Mike and his group have been working on. As we went along Mike explained some of the route’s that have been placed and things of that nature. We arrived at where we were going to be setting up. The first route of the day was Dr. Taco. Mike lead it and set the top rope up for me so I could drag my broken down butt up the rock to try to get some of the kinks worked out. This was a wonderful little Rt. and was a good beginning for the day. After I drug my butt up it Pheobe went up with style and grace cleaning the route and set the top rope anchor through the chains as I should have done my first time up. Then it was Cindy’s turn up which she did very well. At this point we moved on down the crag to where I got to meet Mike F. who was putting in another one of his masterpieces. Mike F. you rock buddy, you are a true rock artist with brass balls to do it from the ground up and solo. Next we went over next to Dr. Taco and did a very nice route with a roof to it. Mike lead this one as well and set the top rope for me. Mike I can’t seem to remember the name to this one, I was having too much fun to write things down, hence I just don’t remember it. I do remember though that I couldn’t drag my ass over the roof even after all the coaching from Pheobe who was belaying for me. Thank you, Pheobe, for the belay and encouragement. Then it was Cindy up the route and over the roof with class and skill for days. Next up on the hit list for the day was Superman, which Mike lead and set the top rope for me. I liked this little route from the ground all the way up to the top. It was even more fun after I peeled off of it while cleaning a little loose rock. I’m sorry again to everyone for not calling the rock coming down and thank you very much Mike for catching me. Even though, I didn’t call falling. It got the heart going and I loved it all the more. There must be something wrong with me that I love the feeling of falling as much as I love climbing. Then It was Cindy and Pheobe up Superman both doing an outstanding job making my struggles look silly I might say. Here we broke for lunch and some wonderful conversation and then we asked Mike F. if we could get on the route that he had just finished bolting. Too which, he said that we could. Thank you again Mike F. This first one up was Pheobe who did an outstanding job with the struggle of this route. Mike, Man this is some sadistic stuff that you put up there. Here are some pictures so you can see for your-self what I’m talking about.

I am sad to report that I hardly got off the ground on this one. I almost achieved the first bolt. But what can I say besides “I’ll be back” again, and again and probably again till I get this one down. I love the line Mike, you did an outstanding job on it. So by the time we got done trying Mike’s line it was getting dark so we packed it in and headed down to the road. This was one of the better days I have had climbing in a while. Thank you to everyone for a warm welcome and a wonderful fun filled day.

I have not been feeling my best in the last week mainly due to the fact that I couldn’t walk from Tuesday to Friday. This is due to the weather change I think. It has been cold and damp here in VA. But Sat I got up and was feeling a little better so after getting out of work at 1730hrs I came home and threw the gear in the truck and got out on the road. I stopped at Wal-Mart to pick up some propane cylinders for my stove and some General Soe’s chicken for my gut and then I was west bound for the Promised Land.

I arrived in smoke hole around 2000hrs and did the link up with mike G at the campfire. This is also where I met Cindy B and Phoebe, who both ROCK. Literally, they are both climber’s. After hanging out at the fire for a while we moved down to the camp site where I talked Mike into helping me set up my new Mountain Hardware tent. Between the two off us we got it set up. One day I will learn to do pre-trip checks on the gear. But we got it set up with no problems. Matt was right this tent rocks. I stayed dry and warm and no condensation at all built up over the night. Ok that was my little plug for Mountain Hardware for this blog. (Mt. Hardware, you can send the check to my Home address) Ok now back to the trip report, after setting up the tent Mike and I did the typical camp thing with everyone and stood around and talked and just had a plain old good time. I had also brought a couple of Magic Hat’s with me in the ruck that I shared with everyone. Magic Hat # 9 has to be one of my favorite beers of all time (Magic Hat, you can also send the check to my home address).

Sunday morning I woke up after one of the best nights of sleep that I have had in a long time. It had to be the river flowing right next to the campsite but I slept very well. After everyone was up Mike, Cindy, and Pheobe went up to Mike’s and I hung out at the campsite and sorted my climbing gear for the day and packed up my tent, fart sack and puss pad. Then I just hung out and enjoyed the wonderful scenery that was all around me. I got some really good pictures of the sun on the rocks and the river. When everyone got back Mike had made breakfast for everyone. I’m here to tell you Mike makes the best breakfast burritos that I have ever had in my whole life. So after filling our stomachs with really good food and coffee it was time to fill the hole in my soul for some new rock. So it was off to SC#7!

We left Eagle and set out for SC#7. After arriving we loaded up the gear and headed up for the crag on the wonderful trail that Mike and his group have been working on. As we went along Mike explained some of the route’s that have been placed and things of that nature. We arrived at where we were going to be setting up. The first route of the day was Dr. Taco. Mike lead it and set the top rope up for me so I could drag my broken down butt up the rock to try to get some of the kinks worked out. This was a wonderful little Rt. and was a good beginning for the day. After I drug my butt up it Pheobe went up with style and grace cleaning the route and set the top rope anchor through the chains as I should have done my first time up. Then it was Cindy’s turn up which she did very well. At this point we moved on down the crag to where I got to meet Mike F. who was putting in another one of his masterpieces. Mike F. you rock buddy, you are a true rock artist with brass balls to do it from the ground up and solo. Next we went over next to Dr. Taco and did a very nice route with a roof to it. Mike lead this one as well and set the top rope for me. Mike I can’t seem to remember the name to this one, I was having too much fun to write things down, hence I just don’t remember it. I do remember though that I couldn’t drag my ass over the roof even after all the coaching from Pheobe who was belaying for me. Thank you, Pheobe, for the belay and encouragement. Then it was Cindy up the route and over the roof with class and skill for days. Next up on the hit list for the day was Superman, which Mike lead and set the top rope for me. I liked this little route from the ground all the way up to the top. It was even more fun after I peeled off of it while cleaning a little loose rock. I’m sorry again to everyone for not calling the rock coming down and thank you very much Mike for catching me. Even though, I didn’t call falling. It got the heart going and I loved it all the more. There must be something wrong with me that I love the feeling of falling as much as I love climbing. Then It was Cindy and Pheobe up Superman both doing an outstanding job making my struggles look silly I might say. Here we broke for lunch and some wonderful conversation and then we asked Mike F. if we could get on the route that he had just finished bolting. Too which, he said that we could. Thank you again Mike F. This first one up was Pheobe who did an outstanding job with the struggle of this route. Mike, Man this is some sadistic stuff that you put up there. Here are some pictures so you can see for your-self what I’m talking about.

I am sad to report that I hardly got off the ground on this one. I almost achieved the first bolt. But what can I say besides “I’ll be back” again, and again and probably again till I get this one down. I love the line Mike, you did an outstanding job on it. So by the time we got done trying Mike’s line it was getting dark so we packed it in and headed down to the road. This was one of the better days I have had climbing in a while. Thank you to everyone for a warm welcome and a wonderful fun filled day.

Monday, November 22, 2010

Friday, November 19, 2010

Ronin's Road: Trip Like I Do

Ronin's Road: Trip Like I Do: "The video that started it all... a quick tour of some of the wonderlands you humble author will be camping, exploring and developing this ..."

How our vertical world is rated

Rock Climbing Ratings - from 5.0 to Spiderman

Understand how climbs are rated and learn more about the Yosemite Decimal Rating System.

CLIMBING RATINGS — In the 1950’s a group called the Sierra Club modified an old system which they used to rate climbs according to their difficulty. This system is now called The Yosemite Decimal Rating System.

The YDRS breaks climbing down into classes and grades. Nearly every climbing guide uses this system. Beginning climbers can use this system to find climbs that are challenging but not too difficult; preventing them from venturing out onto something too hard that might lead to injury.

All climbing, hiking, crawling, and so on can be broken down into these classes. A brief explanation of the classes will describe what type of climbing might be encountered.

Class 1 : Walking, on an established trail.

Class 2 : Hiking, up a steep incline, possibly using your hands for balance.

Class 3 : Climbing up a steep hillside; a rope is not normally used.

Class 4 : Exposed climbing, following a ledge system for example. A rope would be used to belay past places where a fall could be lethal.

Class 5 : This is where technical rock climbing begins. A 3 point stance (Two hands and a foot or two feet and a hand) is needed. A rope and protection are needed to safeguard a fall by the person leading. Any unprotected fall from a class 5 climb would be harmful if not fatal. Class 5 climbs are subdivided into categories to give more detail.

5.0-5.4: Climbing up a ramp or a steep section with good holds.

5.5-5.7: Steeper, more vertical climbing, but still on good holds. These routes are also easily protected.

5.8 +/- Vertical climbing on small holds. A + means that the climbing is more sustained like a 5.9, but the route would still be considered a 5.8. If you see a – after the 5.8 rating it means that the climb only has one or two moves like a solid 5.8 would have, but more resembles a 5.7. The + and – are becoming outdated and most guide books have discontinued their use.

5.9 +/- This rating means that the climb might be slightly overhung or may have fairly sustained climbing on smaller holds. With practice the beginning climber can climb in the 5.9 range quickly and with confidence.

5.10 a, b, c, d Very sustained climbing. A weekend climber rarely feels comfortable in this range unless they do go EVERY weekend or has some natural talent. The difference between a 5.10 b and a 5.10 c is very noticeable. Most likely the climbs are overhung with small holds and are sustained or require sequential moves.

5.11 a, b, c, d This is the world of the dedicated climber. Expect steep and difficult routes that demand technical climbing and powerful moves.

5.12 a, b, c, d The routes in this range are usually overhanging climbs requiring delicate foot work on thin holds or long routes requiring great balance on little holds.

5.13 a, b, c, d If you can climb upside down on a glass window, these climbs are right up your alley.

5.14 a, b, c, d These climbs are among the hardest in the world.

5.15 a This is as hard as climbing gets, folks. Keep in mind that very few climbers can actually climb at this level, although Spiderman eats these climbs for breakfast.

Climbs are rated by the hardest move on the route. A person who is a solid 5.8 climber theoretically should be able to climb through the crux (the hardest part of the climb) on any route rated 5.8 regardless of the type of rock or area they climb at. That is the theory anyway. Unfortunately, climbs are not rated by a committee of climbers so a particular climb can be off as much as a letter grade or more. Having said that, the majority of climbs you will do will be right on the money.

Since the destiny of every mountain, cliff, boulder, or pebble is to become like the gravel you walk on to get to the climb, know that ALL RATINGS ARE SUBJECTIVE! Weathering of the rock, the sun, wind and extreme temperatures all contribute to making climbs harder or easier than the rating given to a climb the first time it is established.

While routes are given ratings so you don’t bite off more than you can chew, try climbing at your level and then a little bit more. You might surprise yourself and actually get up the route in relatively good form.

If you are having trouble with a particular climb, don’t blame the rating. Train a little harder, do a few extra pushups at night, and give it a go again. Climbing is about setting goals and working to achieve them.

The last rating class of the Yosemite Decimal Rating System is class 6, which is considered aid climbing. Aid climbing has its own rating system that does not use decimals like class 5. Instead it uses A to abbreviate Aid and then a number which indicates how challenging the moves are and the commitment level involved on the climb. For more information see the article on Aid Climbing.

Understand how climbs are rated and learn more about the Yosemite Decimal Rating System.

CLIMBING RATINGS — In the 1950’s a group called the Sierra Club modified an old system which they used to rate climbs according to their difficulty. This system is now called The Yosemite Decimal Rating System.

The YDRS breaks climbing down into classes and grades. Nearly every climbing guide uses this system. Beginning climbers can use this system to find climbs that are challenging but not too difficult; preventing them from venturing out onto something too hard that might lead to injury.

All climbing, hiking, crawling, and so on can be broken down into these classes. A brief explanation of the classes will describe what type of climbing might be encountered.

Class 1 : Walking, on an established trail.

Class 2 : Hiking, up a steep incline, possibly using your hands for balance.

Class 3 : Climbing up a steep hillside; a rope is not normally used.

Class 4 : Exposed climbing, following a ledge system for example. A rope would be used to belay past places where a fall could be lethal.

Class 5 : This is where technical rock climbing begins. A 3 point stance (Two hands and a foot or two feet and a hand) is needed. A rope and protection are needed to safeguard a fall by the person leading. Any unprotected fall from a class 5 climb would be harmful if not fatal. Class 5 climbs are subdivided into categories to give more detail.

5.0-5.4: Climbing up a ramp or a steep section with good holds.

5.5-5.7: Steeper, more vertical climbing, but still on good holds. These routes are also easily protected.

5.8 +/- Vertical climbing on small holds. A + means that the climbing is more sustained like a 5.9, but the route would still be considered a 5.8. If you see a – after the 5.8 rating it means that the climb only has one or two moves like a solid 5.8 would have, but more resembles a 5.7. The + and – are becoming outdated and most guide books have discontinued their use.

5.9 +/- This rating means that the climb might be slightly overhung or may have fairly sustained climbing on smaller holds. With practice the beginning climber can climb in the 5.9 range quickly and with confidence.

5.10 a, b, c, d Very sustained climbing. A weekend climber rarely feels comfortable in this range unless they do go EVERY weekend or has some natural talent. The difference between a 5.10 b and a 5.10 c is very noticeable. Most likely the climbs are overhung with small holds and are sustained or require sequential moves.

5.11 a, b, c, d This is the world of the dedicated climber. Expect steep and difficult routes that demand technical climbing and powerful moves.

5.12 a, b, c, d The routes in this range are usually overhanging climbs requiring delicate foot work on thin holds or long routes requiring great balance on little holds.

5.13 a, b, c, d If you can climb upside down on a glass window, these climbs are right up your alley.

5.14 a, b, c, d These climbs are among the hardest in the world.

5.15 a This is as hard as climbing gets, folks. Keep in mind that very few climbers can actually climb at this level, although Spiderman eats these climbs for breakfast.

Climbs are rated by the hardest move on the route. A person who is a solid 5.8 climber theoretically should be able to climb through the crux (the hardest part of the climb) on any route rated 5.8 regardless of the type of rock or area they climb at. That is the theory anyway. Unfortunately, climbs are not rated by a committee of climbers so a particular climb can be off as much as a letter grade or more. Having said that, the majority of climbs you will do will be right on the money.

Since the destiny of every mountain, cliff, boulder, or pebble is to become like the gravel you walk on to get to the climb, know that ALL RATINGS ARE SUBJECTIVE! Weathering of the rock, the sun, wind and extreme temperatures all contribute to making climbs harder or easier than the rating given to a climb the first time it is established.

While routes are given ratings so you don’t bite off more than you can chew, try climbing at your level and then a little bit more. You might surprise yourself and actually get up the route in relatively good form.

If you are having trouble with a particular climb, don’t blame the rating. Train a little harder, do a few extra pushups at night, and give it a go again. Climbing is about setting goals and working to achieve them.

The last rating class of the Yosemite Decimal Rating System is class 6, which is considered aid climbing. Aid climbing has its own rating system that does not use decimals like class 5. Instead it uses A to abbreviate Aid and then a number which indicates how challenging the moves are and the commitment level involved on the climb. For more information see the article on Aid Climbing.

Freezing To Death

As Freezing Persons Recollect the Snow--First Chill--Then Stupor--Then the Letting Go

Outside magazine, January 1997

As Freezing Persons Recollect the Snow--First Chill--Then Stupor--Then the Letting Go

The cold hard facts of freezing to death

By Peter Stark

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

When your Jeep spins lazily off the mountain road and slams backward into a snowbank, you don't worry immediately about the cold. Your first thought is that you've just dented your bumper. Your second is that you've failed to bring a shovel. Your third is that you'll be late for dinner. Friends are expecting you at their cabin around eight for a moonlight ski, a late dinner, a sauna. Nothing can keep you from that.

Driving out of town, defroster roaring, you barely noted the bank thermometer on the town square: minus 27 degrees at 6:36. The radio weather report warned of a deep mass of arctic air settling over the region. The man who took your money at the Conoco station shook his head at the register and said he wouldn't be going anywhere tonight if he were you. You smiled. A little chill never hurt anybody with enough fleece and a good four-wheel-drive.

But now you're stuck. Jamming the gearshift into low, you try to muscle out of the drift. The tires whine on ice-slicked snow as headlights dance on the curtain of frosted firs across the road. Shoving the lever back into park, you shoulder open the door and step from your heated capsule. Cold slaps your naked face, squeezes tears from your eyes.

You check your watch: 7:18. You consult your map: A thin, switchbacking line snakes up the mountain to the penciled square that marks the cabin.

Breath rolls from you in short frosted puffs. The Jeep lies cocked sideways in the snowbank like an empty turtle shell. You think of firelight and saunas and warm food and wine. You look again at the map. It's maybe five or six miles more to that penciled square. You run that far every day before breakfast. You'll just put on your skis. No problem.

There is no precise core temperature at which the human body perishes from cold. At Dachau's cold-water immersion baths, Nazi doctors calculated death to arrive at around 77 degrees Fahrenheit. The lowest recorded core temperature in a surviving adult is 60.8 degrees. For a child it's lower: In 1994, a two-year-old girl in Saskatchewan wandered out of her house into a minus-40 night. She was found near her doorstep the next morning, limbs frozen solid, her core temperature 57 degrees. She lived.

Others are less fortunate, even in much milder conditions. One of Europe's worst weather disasters occurred during a 1964 competitive walk on a windy, rainy English moor; three of the racers died from hypothermia, though temperatures never fell below freezing and ranged as high as 45.

But for all scientists and statisticians now know of freezing and its physiology, no one can yet predict exactly how quickly and in whom hypothermia will strike--and whether it will kill when it does. The cold remains a mystery, more prone to fell men than women, more lethal to the thin and well muscled than to those with avoirdupois, and least forgiving to the arrogant and the unaware.

The process begins even before you leave the car, when you remove your gloves to squeeze a loose bail back into one of your ski bindings. The freezing metal bites your flesh. Your skin temperature drops.

Within a few seconds, the palms of your hands are a chilly, painful 60 degrees. Instinctively, the web of surface capillaries on your hands constrict, sending blood coursing away from your skin and deeper into your torso. Your body is allowing your fingers to chill in order to keep its vital organs warm.

You replace your gloves, noticing only that your fingers have numbed slightly. Then you kick boots into bindings and start up the road.

Were you a Norwegian fisherman or Inuit hunter, both of whom frequently work gloveless in the cold, your chilled hands would open their surface capillaries periodically to allow surges of warm blood to pass into them and maintain their flexibility. This phenomenon, known as the hunter's response, can elevate a 35-degree skin temperature to 50 degrees within seven or eight minutes.

Other human adaptations to the cold are more mysterious. Tibetan Buddhist monks can raise the skin temperature of their hands and feet by 15 degrees through meditation. Australian aborigines, who once slept on the ground, unclothed, on near-freezing nights, would slip into a light hypothermic state, suppressing shivering until the rising sun rewarmed them.

You have no such defenses, having spent your days at a keyboard in a climate-controlled office. Only after about ten minutes of hard climbing, as your body temperature rises, does blood start seeping back into your fingers. Sweat trickles down your sternum and spine.

By now you've left the road and decided to shortcut up the forested mountainside to the road's next switchback. Treading slowly through deep, soft snow as the full moon hefts over a spiny ridgetop, throwing silvery bands of moonlight and shadow, you think your friends were right: It's a beautiful night for skiing--though you admit, feeling the minus-30 air bite at your face, it's also cold.

After an hour, there's still no sign of the switchback, and you've begun to worry. You pause to check the map. At this moment, your core temperature reaches its high: 100.8. Climbing in deep snow, you've generated nearly ten times as much body heat as you do when you are resting.

As you step around to orient map to forest, you hear a metallic pop. You look down. The loose bail has disappeared from your binding. You lift your foot and your ski falls from your boot.

You twist on your flashlight, and its cold-weakened batteries throw a yellowish circle in the snow. It's right around here somewhere, you think, as you sift the snow through gloved fingers. Focused so intently on finding the bail, you hardly notice the frigid air pressing against your tired body and sweat-soaked clothes.

The exertion that warmed you on the way uphill now works against you: Your exercise-dilated capillaries carry the excess heat of your core to your skin, and your wet clothing dispels it rapidly into the night. The lack of insulating fat over your muscles allows the cold to creep that much closer to your warm blood.

Your temperature begins to plummet. Within 17 minutes it reaches the normal 98.6. Then it slips below.

At 97 degrees, hunched over in your slow search, the muscles along your neck and shoulders tighten in what's known as pre-shivering muscle tone. Sensors have signaled the temperature control center in your hypothalamus, which in turn has ordered the constriction of the entire web of surface capillaries. Your hands and feet begin to ache with cold. Ignoring the pain, you dig carefully through the snow; another ten minutes pass. Without the bail you know you're in deep trouble.

Finally, nearly 45 minutes later, you find the bail. You even manage to pop it back into its socket and clamp your boot into the binding. But the clammy chill that started around your skin has now wrapped deep into your body's core.

At 95, you've entered the zone of mild hypothermia. You're now trembling violently as your body attains its maximum shivering response, an involuntary condition in which your muscles contract rapidly to generate additional body heat.

It was a mistake, you realize, to come out on a night this cold. You should turn back. Fishing into the front pocket of your shell parka, you fumble out the map. You consulted it to get here; it should be able to guide you back to the warm car. It doesn't occur to you in your increasingly clouded and panicky mental state that you could simply follow your tracks down the way you came.

And after this long stop, the skiing itself has become more difficult. By the time you push off downhill, your muscles have cooled and tightened so dramatically that they no longer contract easily, and once contracted, they won't relax. You're locked into an ungainly, spread-armed, weak-kneed snowplow.

Still, you manage to maneuver between stands of fir, swishing down through silvery light and pools of shadow. You're too cold to think of the beautiful night or of the friends you had meant to see. You think only of the warm Jeep that waits for you somewhere at the bottom of the hill. Its gleaming shell is centered in your mind's eye as you come over the crest of a small knoll. You hear the sudden whistle of wind in your ears as you gain speed. Then, before your mind can quite process what the sight means, you notice a lump in the snow ahead.

Recognizing, slowly, the danger that you are in, you try to jam your skis to a stop. But in your panic, your balance and judgment are poor. Moments later, your ski tips plow into the buried log and you sail headfirst through the air and bellyflop into the snow.

You lie still. There's a dead silence in the forest, broken by the pumping of blood in your ears. Your ankle is throbbing with pain and you've hit your head. You've also lost your hat and a glove. Scratchy snow is packed down your shirt. Meltwater trickles down your neck and spine, joined soon by a thin line of blood from a small cut on your head.

This situation, you realize with an immediate sense of panic, is serious. Scrambling to rise, you collapse in pain, your ankle crumpling beneath you.

As you sink back into the snow, shaken, your heat begins to drain away at an alarming rate, your head alone accounting for 50 percent of the loss. The pain of the cold soon pierces your ears so sharply that you root about in the snow until you find your hat and mash it back onto your head.

But even that little activity has been exhausting. You know you should find your glove as well, and yet you're becoming too weary to feel any urgency. You decide to have a short rest before going on.

An hour passes. at one point, a stray thought says you should start being scared, but fear is a concept that floats somewhere beyond your immediate reach, like that numb hand lying naked in the snow. You've slid into the temperature range at which cold renders the enzymes in your brain less efficient. With every one-degree drop in body temperature below 95, your cerebral metabolic rate falls off by 3 to 5 percent. When your core temperature reaches 93, amnesia nibbles at your consciousness. You check your watch: 12:58. Maybe someone will come looking for you soon. Moments later, you check again. You can't keep the numbers in your head. You'll remember little of what happens next.

Your head drops back. The snow crunches softly in your ear. In the minus-35-degree air, your core temperature falls about one degree every 30 to 40 minutes, your body heat leaching out into the soft, enveloping snow. Apathy at 91 degrees. Stupor at 90.

You've now crossed the boundary into profound hypothermia. By the time your core temperature has fallen to 88 degrees, your body has abandoned the urge to warm itself by shivering. Your blood is thickening like crankcase oil in a cold engine. Your oxygen consumption, a measure of your metabolic rate, has fallen by more than a quarter. Your kidneys, however, work overtime to process the fluid overload that occurred when the blood vessels in your extremities constricted and squeezed fluids toward your center. You feel a powerful urge to urinate, the only thing you feel at all.

By 87 degrees you've lost the ability to recognize a familiar face, should one suddenly appear from the woods.

At 86 degrees, your heart, its electrical impulses hampered by chilled nerve tissues, becomes arrhythmic. It now pumps less than two-thirds the normal amount of blood. The lack of oxygen and the slowing metabolism of your brain, meanwhile, begin to trigger visual and auditory hallucinations.

You hear jingle bells. Lifting your face from your snow pillow, you realize with a surge of gladness that they're not sleigh bells; they're welcoming bells hanging from the door of your friends' cabin. You knew it had to be close by. The jingling is the sound of the cabin door opening, just through the fir trees.

Attempting to stand, you collapse in a tangle of skis and poles. That's OK. You can crawl. It's so close.

Hours later, or maybe it's minutes, you realize the cabin still sits beyond the grove of trees. You've crawled only a few feet. The light on your wristwatch pulses in the darkness: 5:20. Exhausted, you decide to rest your head for a moment.

When you lift it again, you're inside, lying on the floor before the woodstove. The fire throws off a red glow. First it's warm; then it's hot; then it's searing your flesh. Your clothing has caught fire.

At 85 degrees, those freezing to death, in a strange, anguished paroxysm, often rip off their clothes. This phenomenon, known as paradoxical undressing, is common enough that urban hypothermia victims are sometimes initially diagnosed as victims of sexual assault. Though researchers are uncertain of the cause, the most logical explanation is that shortly before loss of consciousness, the constricted blood vessels near the body's surface suddenly dilate and produce a sensation of extreme heat against the skin.

All you know is that you're burning. You claw off your shell and pile sweater and fling them away.

But then, in a final moment of clarity, you realize there's no stove, no cabin, no friends. You're lying alone in the bitter cold, naked from the waist up. You grasp your terrible misunderstanding, a whole series of misunderstandings, like a dream ratcheting into wrongness. You've shed your clothes, your car, your oil-heated house in town. Without this ingenious technology you're simply a delicate, tropical organism whose range is restricted to a narrow sunlit band that girds the earth at the equator.

And you've now ventured way beyond it.

There's an adage about hypothermia: "You aren't dead until you're warm and dead."

At about 6:00 the next morning, his friends, having discovered the stalled Jeep, find him, still huddled inches from the buried log, his gloveless hand shoved into his armpit. The flesh of his limbs is waxy and stiff as old putty, his pulse nonexistent, his pupils unresponsive to light. Dead.

But those who understand cold know that even as it deadens, it offers perverse salvation. Heat is a presence: the rapid vibrating of molecules. Cold is an absence: the damping of the vibrations. At absolute zero, minus 459.67 degrees Fahrenheit, molecular motion ceases altogether. It is this slowing that converts gases to liquids, liquids to solids, and renders solids harder. It slows bacterial growth and chemical reactions. In the human body, cold shuts down metabolism. The lungs take in less oxygen, the heart pumps less blood. Under normal temperatures, this would produce brain damage. But the chilled brain, having slowed its own metabolism, needs far less oxygen-rich blood and can, under the right circumstances, survive intact.

Setting her ear to his chest, one of his rescuers listens intently. Seconds pass. Then, faintly, she hears a tiny sound--a single thump, so slight that it might be the sound of her own blood. She presses her ear harder to the cold flesh. Another faint thump, then another.

The slowing that accompanies freezing is, in its way, so beneficial that it is even induced at times. Cardiologists today often use deep chilling to slow a patient's metabolism in preparation for heart or brain surgery. In this state of near suspension, the patient's blood flows slowly, his heart rarely beats--or in the case of those on heart-lung machines, doesn't beat at all; death seems near. But carefully monitored, a patient can remain in this cold stasis, undamaged, for hours.

The rescuers quickly wrap their friend's naked torso with a spare parka, his hands with mittens, his entire body with a bivy sack. They brush snow from his pasty, frozen face. Then one snakes down through the forest to the nearest cabin. The others, left in the pre-dawn darkness, huddle against him as silence closes around them. For a moment, the woman imagines she can hear the scurrying, breathing, snoring of a world of creatures that have taken cover this frigid night beneath the thick quilt of snow.

With a "one, two, three," the doctor and nurses slide the man's stiff, curled form onto a table fitted with a mattress filled with warm water which will be regularly reheated. They'd been warned that they had a profound hypothermia case coming in. Usually such victims can be straightened from their tortured fetal positions. This one can't.

Technicians scissor with stainless-steel shears at the man's urine-soaked long underwear and shell pants, frozen together like corrugated cardboard. They attach heart-monitor electrodes to his chest and insert a low-temperature electronic thermometer into his rectum. Digital readings flash: 24 beats per minute and a core temperature of 79.2 degrees.

The doctor shakes his head. He can't remember seeing numbers so low. He's not quite sure how to revive this man without killing him.

In fact, many hypothermia victims die each year in the process of being rescued. In "rewarming shock," the constricted capillaries reopen almost all at once, causing a sudden drop in blood pressure. The slightest movement can send a victim's heart muscle into wild spasms of ventricular fibrillation. In 1980, 16 shipwrecked Danish fishermen were hauled to safety after an hour and a half in the frigid North Sea. They then walked across the deck of the rescue ship, stepped below for a hot drink, and dropped dead, all 16 of them.

"78.9," a technician calls out. "That's three-tenths down."

The patient is now experiencing "afterdrop," in which residual cold close to the body's surface continues to cool the core even after the victim is removed from the outdoors.

The doctor rapidly issues orders to his staff: intravenous administration of warm saline, the bag first heated in the microwave to 110 degrees. Elevating the core temperature of an average-size male one degree requires adding about 60 kilocalories of heat. A kilocalorie is the amount of heat needed to raise the temperature of one liter of water one degree Celsius. Since a quart of hot soup at 140 degrees offers about 30 kilocalories, the patient curled on the table would need to consume 40 quarts of chicken broth to push his core temperature up to normal. Even the warm saline, infused directly into his blood, will add only 30 kilocalories.

Ideally, the doctor would have access to a cardiopulmonary bypass machine, with which he could pump out the victim's blood, rewarm and oxygenate it, and pump it back in again, safely raising the core temperature as much as one degree every three minutes. But such machines are rarely available outside major urban hospitals. Here, without such equipment, the doctor must rely on other options.

"Let's scrub for surgery," he calls out.

Moments later, he's sliding a large catheter into an incision in the man's abdominal cavity. Warm fluid begins to flow from a suspended bag, washing through his abdomen, and draining out through another catheter placed in another incision. Prosaically, this lavage operates much like a car radiator in reverse: The solution warms the internal organs, and the warm blood in the organs is then pumped by the heart throughout the body.

The patient's stiff limbs begin to relax. His pulse edges up. But even so the jagged line of his heartbeat flashing across the EKG screen shows the curious dip known as a J wave, common to hypothermia patients.

"Be ready to defibrillate," the doctor warns the EMTs.

For another hour, nurses and EMTs hover around the edges of the table where the patient lies centered in a warm pool of light, as if offered up to the sun god. They check his heart. They check the heat of the mattress beneath him. They whisper to one another about the foolishness of having gone out alone tonight.

And slowly the patient responds. Another liter of saline is added to the IV. The man's blood pressure remains far too low, brought down by the blood flowing out to the fast-opening capillaries of his limbs. Fluid lost through perspiration and urination has reduced his blood volume. But every 15 or 20 minutes, his temperature rises another degree. The immediate danger of cardiac fibrillation lessens, as the heart and thinning blood warms. Frostbite could still cost him fingers or an earlobe. But he appears to have beaten back the worst of the frigidity.

For the next half hour, an EMT quietly calls the readouts of the thermometer, a mantra that marks the progress of this cold-blooded proto-organism toward a state of warmer, higher consciousness.

"90.4...

"92.2..."

From somewhere far away in the immense, cold darkness, you hear a faint, insistent hum. Quickly it mushrooms into a ball of sound, like a planet rushing toward you, and then it becomes a stream of words.

A voice is calling your name.

You don't want to open your eyes. You sense heat and light playing against your eyelids, but beneath their warm dance a chill wells up inside you from the sunless ocean bottoms and the farthest depths of space. You are too tired even to shiver. You want only to sleep.

"Can you hear me?"

You force open your eyes. Lights glare overhead. Around the lights faces hover atop uniformed bodies. You try to think: You've been away a very long time, but where have you been?

"You're at the hospital. You got caught in the cold."

You try to nod. Your neck muscles feel rusted shut, unused for years. They respond to your command with only a slight twitch.

"You'll probably have amnesia," the voice says.

You remember the moon rising over the spiky ridgetop and skiing up toward it, toward someplace warm beneath the frozen moon. After that, nothing--only that immense coldness lodged inside you.

"We're trying to get a little warmth back into you," the voice says.

You'd nod if you could. But you can't move. All you can feel is throbbing discomfort everywhere. Glancing down to where the pain is most biting, you notice blisters filled with clear fluid dotting your fingers, once gloveless in the snow. During the long, cold hours the tissue froze and ice crystals formed in the tiny spaces between your cells, sucking water from them, blocking the blood supply. You stare at them absently.

"I think they'll be fine," a voice from overhead says. "The damage looks superficial. We expect that the blisters will break in a week or so, and the tissue should revive after that."

If not, you know that your fingers will eventually turn black, the color of bloodless, dead tissue. And then they will be amputated.

But worry slips from you as another wave of exhaustion sweeps in. Slowly you drift off, dreaming of warmth, of tropical ocean wavelets breaking across your chest, of warm sand beneath you.

Hours later, still logy and numb, you surface, as if from deep under water. A warm tide seems to be flooding your midsection. Focusing your eyes down there with difficulty, you see tubes running into you, their heat mingling with your abdomen's depthless cold like a churned-up river. You follow the tubes to the bag that hangs suspended beneath the electric light.

And with a lurch that would be a sob if you could make a sound, you begin to understand: The bag contains all that you had so nearly lost. These people huddled around you have brought you sunlight and warmth, things you once so cavalierly dismissed as constant, available, yours, summoned by the simple twisting of a knob or tossing on of a layer.

But in the hours since you last believed that, you've traveled to a place where there is no sun. You've seen that in the infinite reaches of the universe, heat is as glorious and ephemeral as the light of the stars. Heat exists only where matter exists, where particles can vibrate and jump. In the infinite winter of space, heat is tiny; it is the cold that is huge.

Someone speaks. Your eyes move from bright lights to shadowy forms in the dim outer reaches of the room. You recognize the voice of one of the friends you set out to visit, so long ago now. She's smiling down at you crookedly.

"It's cold out there," she says. "Isn't it?"

Peter Stark is a longtime contributor to Outside. He is the author of Driving to Greenland (Lyons & Burford) and is currently at work on a trilogy of travel memoirs.

Illustrations by Christian Northeast

Copyright 1997, Outside magazine

Outside magazine, January 1997

As Freezing Persons Recollect the Snow--First Chill--Then Stupor--Then the Letting Go

The cold hard facts of freezing to death

By Peter Stark

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

When your Jeep spins lazily off the mountain road and slams backward into a snowbank, you don't worry immediately about the cold. Your first thought is that you've just dented your bumper. Your second is that you've failed to bring a shovel. Your third is that you'll be late for dinner. Friends are expecting you at their cabin around eight for a moonlight ski, a late dinner, a sauna. Nothing can keep you from that.

Driving out of town, defroster roaring, you barely noted the bank thermometer on the town square: minus 27 degrees at 6:36. The radio weather report warned of a deep mass of arctic air settling over the region. The man who took your money at the Conoco station shook his head at the register and said he wouldn't be going anywhere tonight if he were you. You smiled. A little chill never hurt anybody with enough fleece and a good four-wheel-drive.

But now you're stuck. Jamming the gearshift into low, you try to muscle out of the drift. The tires whine on ice-slicked snow as headlights dance on the curtain of frosted firs across the road. Shoving the lever back into park, you shoulder open the door and step from your heated capsule. Cold slaps your naked face, squeezes tears from your eyes.

You check your watch: 7:18. You consult your map: A thin, switchbacking line snakes up the mountain to the penciled square that marks the cabin.

Breath rolls from you in short frosted puffs. The Jeep lies cocked sideways in the snowbank like an empty turtle shell. You think of firelight and saunas and warm food and wine. You look again at the map. It's maybe five or six miles more to that penciled square. You run that far every day before breakfast. You'll just put on your skis. No problem.

There is no precise core temperature at which the human body perishes from cold. At Dachau's cold-water immersion baths, Nazi doctors calculated death to arrive at around 77 degrees Fahrenheit. The lowest recorded core temperature in a surviving adult is 60.8 degrees. For a child it's lower: In 1994, a two-year-old girl in Saskatchewan wandered out of her house into a minus-40 night. She was found near her doorstep the next morning, limbs frozen solid, her core temperature 57 degrees. She lived.

Others are less fortunate, even in much milder conditions. One of Europe's worst weather disasters occurred during a 1964 competitive walk on a windy, rainy English moor; three of the racers died from hypothermia, though temperatures never fell below freezing and ranged as high as 45.

But for all scientists and statisticians now know of freezing and its physiology, no one can yet predict exactly how quickly and in whom hypothermia will strike--and whether it will kill when it does. The cold remains a mystery, more prone to fell men than women, more lethal to the thin and well muscled than to those with avoirdupois, and least forgiving to the arrogant and the unaware.

The process begins even before you leave the car, when you remove your gloves to squeeze a loose bail back into one of your ski bindings. The freezing metal bites your flesh. Your skin temperature drops.

Within a few seconds, the palms of your hands are a chilly, painful 60 degrees. Instinctively, the web of surface capillaries on your hands constrict, sending blood coursing away from your skin and deeper into your torso. Your body is allowing your fingers to chill in order to keep its vital organs warm.

You replace your gloves, noticing only that your fingers have numbed slightly. Then you kick boots into bindings and start up the road.

Were you a Norwegian fisherman or Inuit hunter, both of whom frequently work gloveless in the cold, your chilled hands would open their surface capillaries periodically to allow surges of warm blood to pass into them and maintain their flexibility. This phenomenon, known as the hunter's response, can elevate a 35-degree skin temperature to 50 degrees within seven or eight minutes.

Other human adaptations to the cold are more mysterious. Tibetan Buddhist monks can raise the skin temperature of their hands and feet by 15 degrees through meditation. Australian aborigines, who once slept on the ground, unclothed, on near-freezing nights, would slip into a light hypothermic state, suppressing shivering until the rising sun rewarmed them.

You have no such defenses, having spent your days at a keyboard in a climate-controlled office. Only after about ten minutes of hard climbing, as your body temperature rises, does blood start seeping back into your fingers. Sweat trickles down your sternum and spine.

By now you've left the road and decided to shortcut up the forested mountainside to the road's next switchback. Treading slowly through deep, soft snow as the full moon hefts over a spiny ridgetop, throwing silvery bands of moonlight and shadow, you think your friends were right: It's a beautiful night for skiing--though you admit, feeling the minus-30 air bite at your face, it's also cold.

After an hour, there's still no sign of the switchback, and you've begun to worry. You pause to check the map. At this moment, your core temperature reaches its high: 100.8. Climbing in deep snow, you've generated nearly ten times as much body heat as you do when you are resting.

As you step around to orient map to forest, you hear a metallic pop. You look down. The loose bail has disappeared from your binding. You lift your foot and your ski falls from your boot.

You twist on your flashlight, and its cold-weakened batteries throw a yellowish circle in the snow. It's right around here somewhere, you think, as you sift the snow through gloved fingers. Focused so intently on finding the bail, you hardly notice the frigid air pressing against your tired body and sweat-soaked clothes.

The exertion that warmed you on the way uphill now works against you: Your exercise-dilated capillaries carry the excess heat of your core to your skin, and your wet clothing dispels it rapidly into the night. The lack of insulating fat over your muscles allows the cold to creep that much closer to your warm blood.

Your temperature begins to plummet. Within 17 minutes it reaches the normal 98.6. Then it slips below.

At 97 degrees, hunched over in your slow search, the muscles along your neck and shoulders tighten in what's known as pre-shivering muscle tone. Sensors have signaled the temperature control center in your hypothalamus, which in turn has ordered the constriction of the entire web of surface capillaries. Your hands and feet begin to ache with cold. Ignoring the pain, you dig carefully through the snow; another ten minutes pass. Without the bail you know you're in deep trouble.

Finally, nearly 45 minutes later, you find the bail. You even manage to pop it back into its socket and clamp your boot into the binding. But the clammy chill that started around your skin has now wrapped deep into your body's core.

At 95, you've entered the zone of mild hypothermia. You're now trembling violently as your body attains its maximum shivering response, an involuntary condition in which your muscles contract rapidly to generate additional body heat.

It was a mistake, you realize, to come out on a night this cold. You should turn back. Fishing into the front pocket of your shell parka, you fumble out the map. You consulted it to get here; it should be able to guide you back to the warm car. It doesn't occur to you in your increasingly clouded and panicky mental state that you could simply follow your tracks down the way you came.

And after this long stop, the skiing itself has become more difficult. By the time you push off downhill, your muscles have cooled and tightened so dramatically that they no longer contract easily, and once contracted, they won't relax. You're locked into an ungainly, spread-armed, weak-kneed snowplow.

Still, you manage to maneuver between stands of fir, swishing down through silvery light and pools of shadow. You're too cold to think of the beautiful night or of the friends you had meant to see. You think only of the warm Jeep that waits for you somewhere at the bottom of the hill. Its gleaming shell is centered in your mind's eye as you come over the crest of a small knoll. You hear the sudden whistle of wind in your ears as you gain speed. Then, before your mind can quite process what the sight means, you notice a lump in the snow ahead.

Recognizing, slowly, the danger that you are in, you try to jam your skis to a stop. But in your panic, your balance and judgment are poor. Moments later, your ski tips plow into the buried log and you sail headfirst through the air and bellyflop into the snow.

You lie still. There's a dead silence in the forest, broken by the pumping of blood in your ears. Your ankle is throbbing with pain and you've hit your head. You've also lost your hat and a glove. Scratchy snow is packed down your shirt. Meltwater trickles down your neck and spine, joined soon by a thin line of blood from a small cut on your head.

This situation, you realize with an immediate sense of panic, is serious. Scrambling to rise, you collapse in pain, your ankle crumpling beneath you.

As you sink back into the snow, shaken, your heat begins to drain away at an alarming rate, your head alone accounting for 50 percent of the loss. The pain of the cold soon pierces your ears so sharply that you root about in the snow until you find your hat and mash it back onto your head.

But even that little activity has been exhausting. You know you should find your glove as well, and yet you're becoming too weary to feel any urgency. You decide to have a short rest before going on.

An hour passes. at one point, a stray thought says you should start being scared, but fear is a concept that floats somewhere beyond your immediate reach, like that numb hand lying naked in the snow. You've slid into the temperature range at which cold renders the enzymes in your brain less efficient. With every one-degree drop in body temperature below 95, your cerebral metabolic rate falls off by 3 to 5 percent. When your core temperature reaches 93, amnesia nibbles at your consciousness. You check your watch: 12:58. Maybe someone will come looking for you soon. Moments later, you check again. You can't keep the numbers in your head. You'll remember little of what happens next.

Your head drops back. The snow crunches softly in your ear. In the minus-35-degree air, your core temperature falls about one degree every 30 to 40 minutes, your body heat leaching out into the soft, enveloping snow. Apathy at 91 degrees. Stupor at 90.

You've now crossed the boundary into profound hypothermia. By the time your core temperature has fallen to 88 degrees, your body has abandoned the urge to warm itself by shivering. Your blood is thickening like crankcase oil in a cold engine. Your oxygen consumption, a measure of your metabolic rate, has fallen by more than a quarter. Your kidneys, however, work overtime to process the fluid overload that occurred when the blood vessels in your extremities constricted and squeezed fluids toward your center. You feel a powerful urge to urinate, the only thing you feel at all.

By 87 degrees you've lost the ability to recognize a familiar face, should one suddenly appear from the woods.

At 86 degrees, your heart, its electrical impulses hampered by chilled nerve tissues, becomes arrhythmic. It now pumps less than two-thirds the normal amount of blood. The lack of oxygen and the slowing metabolism of your brain, meanwhile, begin to trigger visual and auditory hallucinations.

You hear jingle bells. Lifting your face from your snow pillow, you realize with a surge of gladness that they're not sleigh bells; they're welcoming bells hanging from the door of your friends' cabin. You knew it had to be close by. The jingling is the sound of the cabin door opening, just through the fir trees.

Attempting to stand, you collapse in a tangle of skis and poles. That's OK. You can crawl. It's so close.

Hours later, or maybe it's minutes, you realize the cabin still sits beyond the grove of trees. You've crawled only a few feet. The light on your wristwatch pulses in the darkness: 5:20. Exhausted, you decide to rest your head for a moment.

When you lift it again, you're inside, lying on the floor before the woodstove. The fire throws off a red glow. First it's warm; then it's hot; then it's searing your flesh. Your clothing has caught fire.

At 85 degrees, those freezing to death, in a strange, anguished paroxysm, often rip off their clothes. This phenomenon, known as paradoxical undressing, is common enough that urban hypothermia victims are sometimes initially diagnosed as victims of sexual assault. Though researchers are uncertain of the cause, the most logical explanation is that shortly before loss of consciousness, the constricted blood vessels near the body's surface suddenly dilate and produce a sensation of extreme heat against the skin.

All you know is that you're burning. You claw off your shell and pile sweater and fling them away.

But then, in a final moment of clarity, you realize there's no stove, no cabin, no friends. You're lying alone in the bitter cold, naked from the waist up. You grasp your terrible misunderstanding, a whole series of misunderstandings, like a dream ratcheting into wrongness. You've shed your clothes, your car, your oil-heated house in town. Without this ingenious technology you're simply a delicate, tropical organism whose range is restricted to a narrow sunlit band that girds the earth at the equator.

And you've now ventured way beyond it.

There's an adage about hypothermia: "You aren't dead until you're warm and dead."

At about 6:00 the next morning, his friends, having discovered the stalled Jeep, find him, still huddled inches from the buried log, his gloveless hand shoved into his armpit. The flesh of his limbs is waxy and stiff as old putty, his pulse nonexistent, his pupils unresponsive to light. Dead.

But those who understand cold know that even as it deadens, it offers perverse salvation. Heat is a presence: the rapid vibrating of molecules. Cold is an absence: the damping of the vibrations. At absolute zero, minus 459.67 degrees Fahrenheit, molecular motion ceases altogether. It is this slowing that converts gases to liquids, liquids to solids, and renders solids harder. It slows bacterial growth and chemical reactions. In the human body, cold shuts down metabolism. The lungs take in less oxygen, the heart pumps less blood. Under normal temperatures, this would produce brain damage. But the chilled brain, having slowed its own metabolism, needs far less oxygen-rich blood and can, under the right circumstances, survive intact.

Setting her ear to his chest, one of his rescuers listens intently. Seconds pass. Then, faintly, she hears a tiny sound--a single thump, so slight that it might be the sound of her own blood. She presses her ear harder to the cold flesh. Another faint thump, then another.

The slowing that accompanies freezing is, in its way, so beneficial that it is even induced at times. Cardiologists today often use deep chilling to slow a patient's metabolism in preparation for heart or brain surgery. In this state of near suspension, the patient's blood flows slowly, his heart rarely beats--or in the case of those on heart-lung machines, doesn't beat at all; death seems near. But carefully monitored, a patient can remain in this cold stasis, undamaged, for hours.

The rescuers quickly wrap their friend's naked torso with a spare parka, his hands with mittens, his entire body with a bivy sack. They brush snow from his pasty, frozen face. Then one snakes down through the forest to the nearest cabin. The others, left in the pre-dawn darkness, huddle against him as silence closes around them. For a moment, the woman imagines she can hear the scurrying, breathing, snoring of a world of creatures that have taken cover this frigid night beneath the thick quilt of snow.

With a "one, two, three," the doctor and nurses slide the man's stiff, curled form onto a table fitted with a mattress filled with warm water which will be regularly reheated. They'd been warned that they had a profound hypothermia case coming in. Usually such victims can be straightened from their tortured fetal positions. This one can't.

Technicians scissor with stainless-steel shears at the man's urine-soaked long underwear and shell pants, frozen together like corrugated cardboard. They attach heart-monitor electrodes to his chest and insert a low-temperature electronic thermometer into his rectum. Digital readings flash: 24 beats per minute and a core temperature of 79.2 degrees.

The doctor shakes his head. He can't remember seeing numbers so low. He's not quite sure how to revive this man without killing him.

In fact, many hypothermia victims die each year in the process of being rescued. In "rewarming shock," the constricted capillaries reopen almost all at once, causing a sudden drop in blood pressure. The slightest movement can send a victim's heart muscle into wild spasms of ventricular fibrillation. In 1980, 16 shipwrecked Danish fishermen were hauled to safety after an hour and a half in the frigid North Sea. They then walked across the deck of the rescue ship, stepped below for a hot drink, and dropped dead, all 16 of them.

"78.9," a technician calls out. "That's three-tenths down."

The patient is now experiencing "afterdrop," in which residual cold close to the body's surface continues to cool the core even after the victim is removed from the outdoors.

The doctor rapidly issues orders to his staff: intravenous administration of warm saline, the bag first heated in the microwave to 110 degrees. Elevating the core temperature of an average-size male one degree requires adding about 60 kilocalories of heat. A kilocalorie is the amount of heat needed to raise the temperature of one liter of water one degree Celsius. Since a quart of hot soup at 140 degrees offers about 30 kilocalories, the patient curled on the table would need to consume 40 quarts of chicken broth to push his core temperature up to normal. Even the warm saline, infused directly into his blood, will add only 30 kilocalories.

Ideally, the doctor would have access to a cardiopulmonary bypass machine, with which he could pump out the victim's blood, rewarm and oxygenate it, and pump it back in again, safely raising the core temperature as much as one degree every three minutes. But such machines are rarely available outside major urban hospitals. Here, without such equipment, the doctor must rely on other options.

"Let's scrub for surgery," he calls out.

Moments later, he's sliding a large catheter into an incision in the man's abdominal cavity. Warm fluid begins to flow from a suspended bag, washing through his abdomen, and draining out through another catheter placed in another incision. Prosaically, this lavage operates much like a car radiator in reverse: The solution warms the internal organs, and the warm blood in the organs is then pumped by the heart throughout the body.

The patient's stiff limbs begin to relax. His pulse edges up. But even so the jagged line of his heartbeat flashing across the EKG screen shows the curious dip known as a J wave, common to hypothermia patients.

"Be ready to defibrillate," the doctor warns the EMTs.

For another hour, nurses and EMTs hover around the edges of the table where the patient lies centered in a warm pool of light, as if offered up to the sun god. They check his heart. They check the heat of the mattress beneath him. They whisper to one another about the foolishness of having gone out alone tonight.

And slowly the patient responds. Another liter of saline is added to the IV. The man's blood pressure remains far too low, brought down by the blood flowing out to the fast-opening capillaries of his limbs. Fluid lost through perspiration and urination has reduced his blood volume. But every 15 or 20 minutes, his temperature rises another degree. The immediate danger of cardiac fibrillation lessens, as the heart and thinning blood warms. Frostbite could still cost him fingers or an earlobe. But he appears to have beaten back the worst of the frigidity.

For the next half hour, an EMT quietly calls the readouts of the thermometer, a mantra that marks the progress of this cold-blooded proto-organism toward a state of warmer, higher consciousness.

"90.4...

"92.2..."

From somewhere far away in the immense, cold darkness, you hear a faint, insistent hum. Quickly it mushrooms into a ball of sound, like a planet rushing toward you, and then it becomes a stream of words.

A voice is calling your name.

You don't want to open your eyes. You sense heat and light playing against your eyelids, but beneath their warm dance a chill wells up inside you from the sunless ocean bottoms and the farthest depths of space. You are too tired even to shiver. You want only to sleep.

"Can you hear me?"

You force open your eyes. Lights glare overhead. Around the lights faces hover atop uniformed bodies. You try to think: You've been away a very long time, but where have you been?

"You're at the hospital. You got caught in the cold."

You try to nod. Your neck muscles feel rusted shut, unused for years. They respond to your command with only a slight twitch.

"You'll probably have amnesia," the voice says.

You remember the moon rising over the spiky ridgetop and skiing up toward it, toward someplace warm beneath the frozen moon. After that, nothing--only that immense coldness lodged inside you.

"We're trying to get a little warmth back into you," the voice says.

You'd nod if you could. But you can't move. All you can feel is throbbing discomfort everywhere. Glancing down to where the pain is most biting, you notice blisters filled with clear fluid dotting your fingers, once gloveless in the snow. During the long, cold hours the tissue froze and ice crystals formed in the tiny spaces between your cells, sucking water from them, blocking the blood supply. You stare at them absently.

"I think they'll be fine," a voice from overhead says. "The damage looks superficial. We expect that the blisters will break in a week or so, and the tissue should revive after that."

If not, you know that your fingers will eventually turn black, the color of bloodless, dead tissue. And then they will be amputated.

But worry slips from you as another wave of exhaustion sweeps in. Slowly you drift off, dreaming of warmth, of tropical ocean wavelets breaking across your chest, of warm sand beneath you.

Hours later, still logy and numb, you surface, as if from deep under water. A warm tide seems to be flooding your midsection. Focusing your eyes down there with difficulty, you see tubes running into you, their heat mingling with your abdomen's depthless cold like a churned-up river. You follow the tubes to the bag that hangs suspended beneath the electric light.

And with a lurch that would be a sob if you could make a sound, you begin to understand: The bag contains all that you had so nearly lost. These people huddled around you have brought you sunlight and warmth, things you once so cavalierly dismissed as constant, available, yours, summoned by the simple twisting of a knob or tossing on of a layer.

But in the hours since you last believed that, you've traveled to a place where there is no sun. You've seen that in the infinite reaches of the universe, heat is as glorious and ephemeral as the light of the stars. Heat exists only where matter exists, where particles can vibrate and jump. In the infinite winter of space, heat is tiny; it is the cold that is huge.

Someone speaks. Your eyes move from bright lights to shadowy forms in the dim outer reaches of the room. You recognize the voice of one of the friends you set out to visit, so long ago now. She's smiling down at you crookedly.

"It's cold out there," she says. "Isn't it?"

Peter Stark is a longtime contributor to Outside. He is the author of Driving to Greenland (Lyons & Burford) and is currently at work on a trilogy of travel memoirs.

Illustrations by Christian Northeast

Copyright 1997, Outside magazine

Friday, November 12, 2010

Thursday, November 11, 2010

Wednesday, November 10, 2010

Leo's first gear

Leo's first gear, originally uploaded by pyro_mvmc_va.

This is Leo on his first time practicing clearing gear. Yes he is on top rope, This is the safest way to learn the in's and out's of gear in a safe enviroment.

Way to go Brother

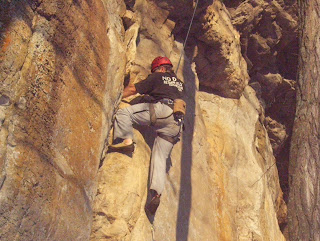

Pyro in Defeat

This was taken right after I got totaly and uterly defeated on a very simple route. I am very pissed at myself here and wondering what the future holds. It was at this point that I really started training to climb again.

Pyro

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)